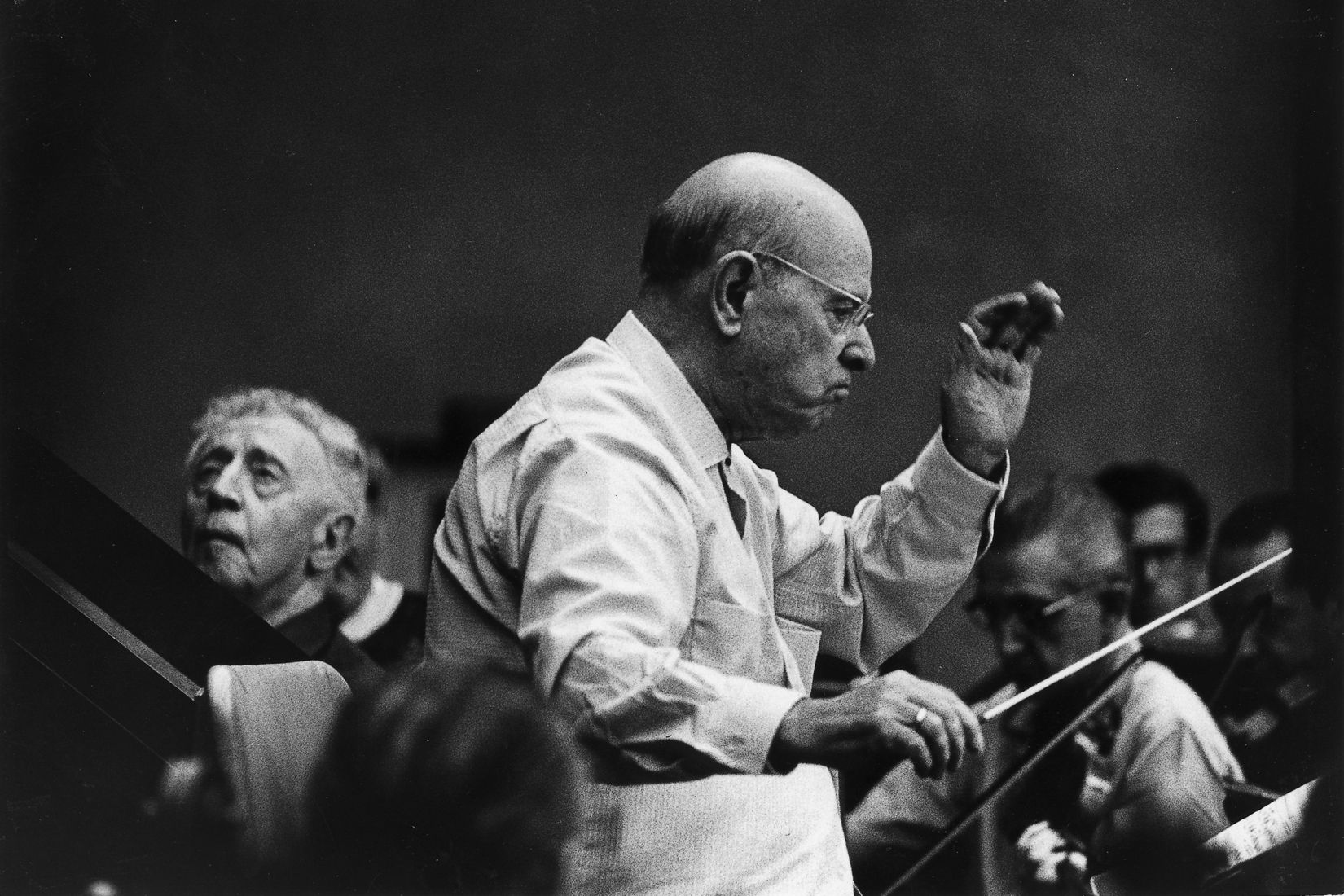

Pablo Casals was an unconventional conductor. Nevertheless, he was a great conductor. Previously recognised as a brilliant cellist, he was a self-taught conductor with a genuine and original way of communicating with musicians. The musical advisor to the Pau Casals Foundation, Bernard Meiller, describes this unique facet of the maestro.

Pablo Casals was an innovator in cello playing technique and a virtuoso who made his mark on the history of this instrument. However, his role as a performer was associated from the outset with that of composer and orchestra conductor. Casals was therefore a total musician.

His vocation as a conductor appeared to him at a very young age inseparably with his discovery of musical performance and composition. The musician was already aware that he had a vocation as a conductor when he was only five years old! He had just joined the parish choir of El Vendrell, run by his father, and since then he wanted to teach other singers how to sing!

In 1898, when he was not yet 22 years old, Pablo Casals took his first steps as a conductor by conducting part of the rehearsals of María del Carmen, the first opera by his friend Enric Granados. Until the end of the First World War, he had few opportunities to conduct, since he was too busy with his activities as a cellist. He conducted his first concert in Paris in 1908, conducting Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony with the Orchestre Lamoureux. His frenetic activity as a cellist, with an incredibly busy schedule of concerts in Europe and America, did not allow him to devote himself to his other great musical passion: orchestral conducting.

It was not until the founding of the Pablo Casals Orchestra that his career as a conductor took a different turn, since from then on conducting occupied about half of his time. He made his debut at Carnegie Hall in 1922, in London with the London Symphony Orchestra in 1925, and in Vienna with the Wiener Philharmoniker in 1927. The public was enthusiastic, but the press was more divided. Some were unhappy that a soloist, even such a great one, should become a conductor. There were also problems with some orchestras, since Casals was not at all satisfied with a perfunctory performance and forced them to rethink their routine phrasing. Some musicians complained about his way of playing, which they wanted to be more precise.

Casals as a conductor was a self-taught musician who had learned everything from the maestros with whom he had played.

Casals as a conductor was a self-taught man who had learned everything from the great conductors with whom he had played as a soloist. He had taken Hans Richter (1843-1916) as his model, who was himself a disciple of Wagner and a friend of Brahms. Pablo Casals was never a virtuoso baton twirler; his only ambition was to share his love of music and his genius as a performer. Conducting was, for Casals, a supreme joy. The cello had given him enormous satisfaction, but at the cost of a lot of work and suffering (due to the panic that invaded him before each concert). For him the orchestra was the ideal instrument, providing him with an unlimited repertoire and that feeling of shared work, of musical communion, which he loved above all else.

After the Second World War, Casals was only able to regain this happiness at the Festival de Prades, and then only in 1953, since the economic situation did not allow him to assemble an orchestra again. Two more festivals offered him the opportunity to conduct: Puerto Rico from 1957, with an orchestra of an exceptional level, made up of musicians from the greatest American orchestras who had come to have the privilege of being conducted by Casals; and Marlboro from 1960, with a unique blend of experienced musicians and very talented young ones. Apart from these festivals, Casals only conducted orchestras for his oratorio El Pessebre, or in the wake of exceptional occasions, such as the Israel Festival.

With his baton he spoke of the infinite diversity of nature and of the most elementary human feelings.

Outwardly, Casals as a conductor bore little resemblance to Casals as a cellist. Unlike his facet as an instrumentalist, in which he was always immobile, impenetrable while playing the cello, his face and even his body became very expressive. For him, the first quality of a conductor was the ability to communicate, to convince. To do so, he used the word, rather briefly, and always in very simple terms. He referred to the infinite diversity of nature or elementary human feelings. These words would have been commonplace with other directors. But with him, they achieved their purpose, since the musicians were able to grasp the absolute sincerity, the truth. Above all, he sang, tirelessly detailing a phrasing or a rhythm, until he felt that the musicians had understood it.

Pablo Casals demanded that the musicians rehearse a great deal before each concert. In general, he would begin with the complete performance of a work before going into minute detail. He did not hesitate to repeat the same passage many and many times until he was satisfied with the result. Adrian Boult, who went to Barcelona in 1922, observed Casals’ work. He counted as many as 19 repetitions of the chromatic scale in the middle of the scherzo of Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream! Casals always did the same thing, even in the repertoire that was played most often. Moreover, he always deliberately chose a well-known work for his first contacts with an orchestra: the Ride of the Valkyries for the first rehearsal of the Pablo Casals Orchestra in 1920, the A Little Serenade in Perpignan in 1951, or Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony in 1957 in Puerto Rico.

The best way to quickly persuade musicians to follow Casals’ great principles was to recover the masterpieces with a fresh ear, to rethink the picture constantly, far from any mood of routine. The maestro from El Vendrell often claimed that the more you are transported into a work of art, the more reasons you find to marvel at it.

The freedom of musical phrasing and the life of rhythm, of which the score could only give a fixed and imperfect indication, should not be limited on the pretext that the conducting of an orchestra should give priority to order. For Pablo Casals, an orchestra, however large it might be, was not fundamentally different from a chamber music ensemble. Each musician has their place and what matters is to address their sensitivity and their intelligence, so that they bring all their fervour and give the best of themselves. One day, following the first Prades Festival, Casals said that he had never been able to find a satisfactory expression and tempo for the work they were to rehearse, and that they would therefore look for them together.

Making music under these conditions was a unique experience, especially at a time when many conductors behaved like dictators and did not hesitate to humiliate the musicians. Casals asked his colleagues to abandon these practices and to treat the musicians with more humanity, and assured them that there was no need for authoritarianism for orchestral discipline to be perfect. He gave the example of the Pau Casals Orchestra, the musicians of which he considered his own family. That is why the relationship between Casals as a conductor and the musicians of the orchestra was more the result of a complicit dialogue and musical respect than an imposition of an authoritarian nature.

Pablo Casals’ reputation as a conductor was affected by his immense fame as a cellist and by the halt of his international career from 1940 onwards. The few Marlboro recordings were very successful, but it was undoubtedly not until the publication of the Puerto Rico concerts that Casals regained his true place among the greatest conductors of the 20th century.

The writer and personal secretary of Pablo Casals, Josep Maria Corredor, explained that the El Vendrell musician mentioned three conductors of his generation as points of reference, at the antipodes of each other: Wilhem Furtwängler (of whom he later said he was the greatest in the Romantic repertoire), Leopold Stokowski and Arturo Toscanini! Unfortunately, none of the three were able to come to Barcelona. Casalsdid not hesitate, contrary to some of his colleagues who feared that the guest conductors would overshadow the music director, to invite the most important conductors of the interwar period. The first, from 1922 onwards, was Serge Koussevitsky, who shortly afterwards took over the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Later, he gave priority to conductors from the great Germanic tradition: Franz Schalk, Oskar Fried, Clemens Krauss, Erich Kleiber, Fritz Busch, Otto Klemperer…

Another of Casals’ great principles was to invite composers to conduct their own works, and his choice of composers demonstrates his concern to open up the Catalan public to a wide variety of contemporary repertoires: Richard Strauss, Igor Stravinsky, Arnold Schoenberg, Vincent d’Indy, Arthur Honegger … and, of course, numerous Catalan composers. No matter if their conducting technique was not perfect, the composers, for Casals, were the best placed to bring his music to life. And if they felt capable, Casals proposed that they also conduct the works of the great composers of the past. Webern conducted symphonies by Haydn, Mozart, Schubert and Mahler, and Zemlinsky performed Beethoven and Dvorak!